I got a text from Nancy last week. “Finally got a chance to read your blog. One of my faves. Grandmom was a saint. Now I suggest you write about Grandad. ‘Two dollars?! You busted?’”

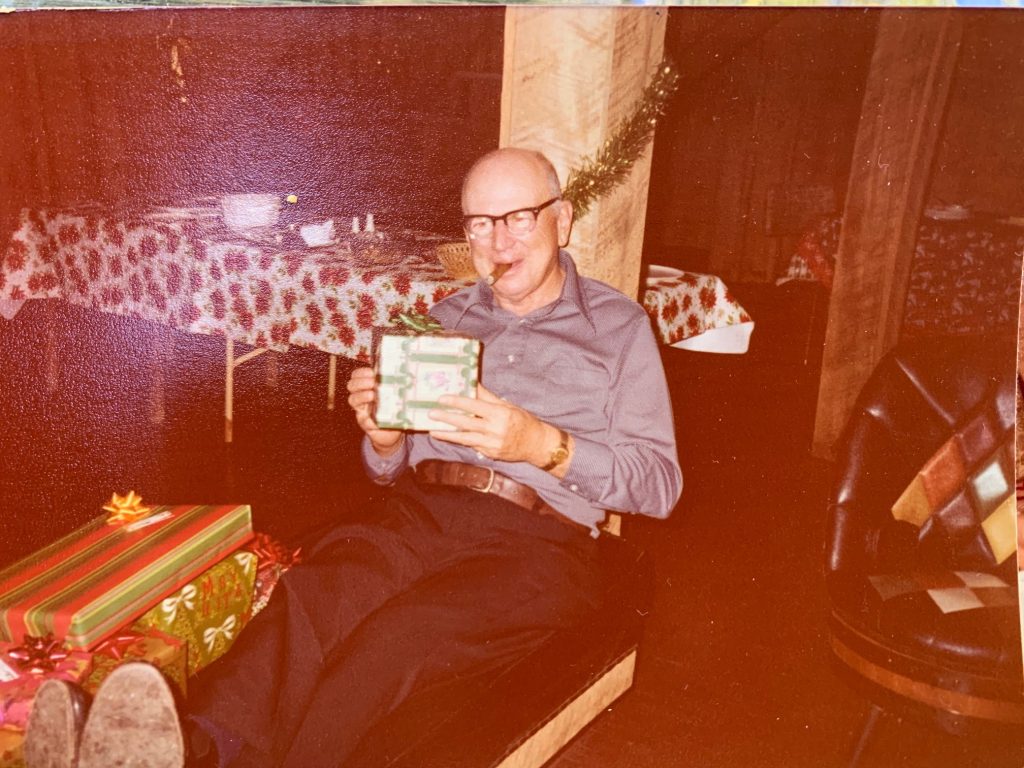

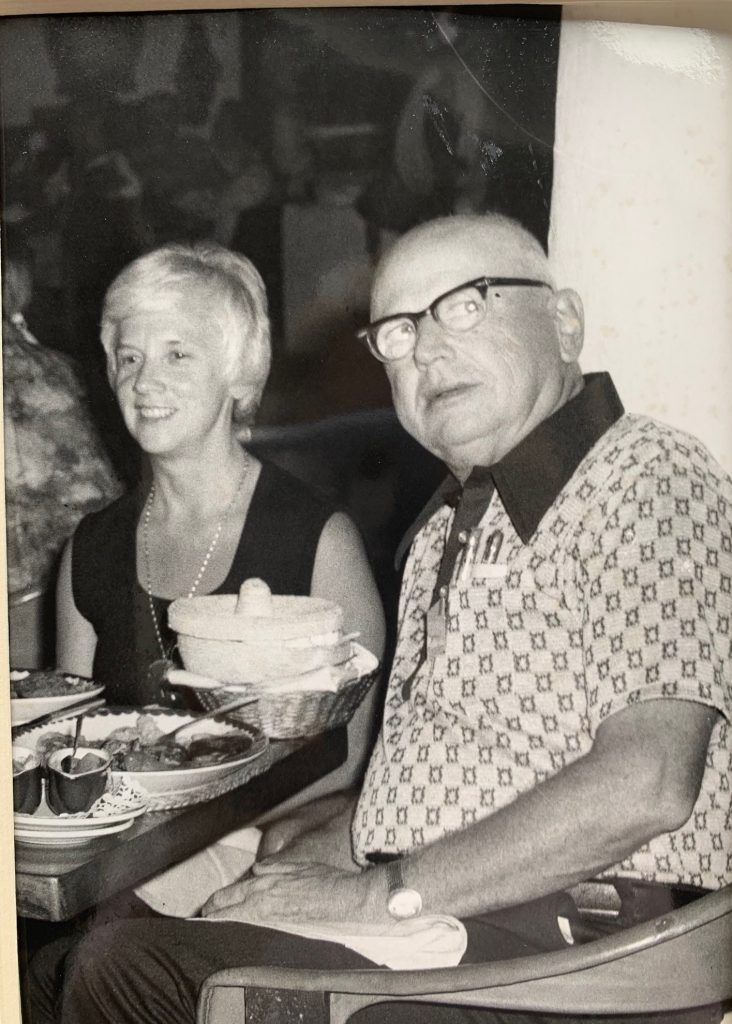

I don’t know if I can effectively describe Grandad in words. I wish I had a Vlog because it’s easier to just do an impression of him, his slow pace, his thick coke bottle glasses on his bald head, his lanky 6’4” frame containing the gentlest of human beings. But most especially his two-word sentences spoken in a no-nonsense western Kentucky accent with hardly any inflection.

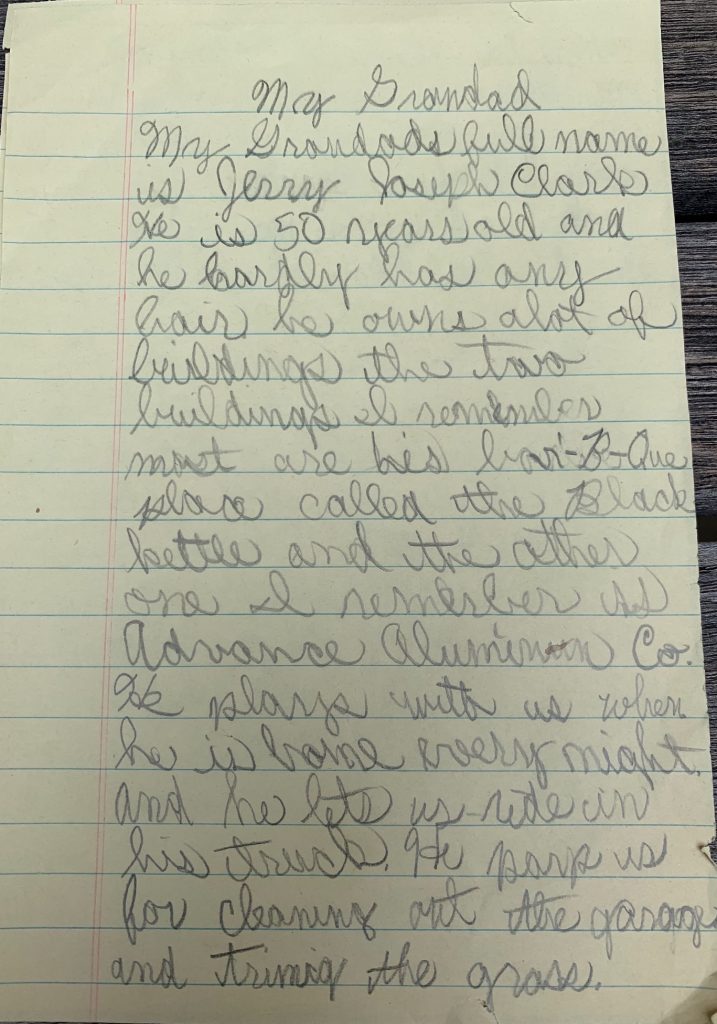

Along with the letter from myself to Grandmom that I found among her keepsakes a few years back, I also discovered that she had saved the first two chapters of the memoir I had begun right after moving in with them when I was nine years old. I only wrote two chapters, the first of which was called My Grandmom. Here’s chapter two:

Grandad always seemed like an old guy. Big, tall, bald, slow-moving, slow-driving, cigar-smoking, dressed always in nondescript short sleeved button-up shirts and brown pants, almost always a cap or a hat.

But he was only fifty years old when Mom showed up on Grandmom and Grandad’s doorstep dragging three girls under the age of nine, all her belongings and a big black Chow Chow named King. Grandad had never lived with kids before. He had been a bachelor until age 35 when he met Grandmom, got married and moved in with her and 17-year-old Mom. He experienced a major lifestyle change that year, 1955, giving up his life of running a bowling alley in Hendersonville, Kentucky and travelling all over the state for bowling tournaments to be a married man in Owensboro. But he’d never experienced a whole-house takeover by three skinny, blonde, energetic little girls, the squealing, the laughing, the yelling and fighting, the constant mess.

Soon after moving into their upstairs bedrooms, my sisters and I were rifling through the bedroom cabinets and had discovered a box of letters and cards Grandad had written to Grandmom during their courting days. A cocktail party was in full swing downstairs when I paraded through the living room, Stacy and Heather in tow, holding Grandad’s letters aloft and giving an inspired dramatic reading of the contents for the whole crowd. “Dear Dorothy, we went all the way up to Louisville for a tournament and I bowled a 225. I’ll be back on Saturday so don’t be mad at me.” He chased us back upstairs, but the damage had been done. We knew he had a romantic side and that these two old folks were once young and in love.

By the time we moved in with them, Grandad owned an aluminum siding company, two farms and several office buildings. He spent his days tending to his business operations, driving from the Advance Aluminum office to schedule a siding job, to The Carlan building to collect some rent, to his farm to tend his tomatoes, to his building on Fifth Street where he rented to a BBQ restaurant. Anyone could spot Grandad. He was the gold Buick ‘88 driving ten miles below the speed limit, arm stuck out the window, looking around at the sights through his thick glasses as if on a tour bus in a foreign place.

Grandad was a man of few words and apparently few emotions. He hardly ever spoke until spoken to and he had a stone-faced demeanor. He was a small-town farm boy through and through. Nobody who knew Jerry Clark would have believed the man he turned into every Tuesday night. The Bowl-a-Drome hosted ladies’ bowling league on Tuesday nights. At 5:00, Mom and Grandmom would don their blue bowling shirts, the pocket of Grandmom’s saying Dot and Mom’s reading Luann, grab their bowling bags and tell us to mind Grandad. As soon as the ladies left, Grandad started the popcorn popping on the stove. He loved popcorn so much that he’d do a little dance to the rhythm of the popping, clapping his hands, hooting and shuffling his feet, faster with the speed of the pops. In his boxer shorts. His exuberance rubbed off and soon we would be over-stimulated and getting into some kind of mischief. We’d be running circles around the house with King at our heels barking excitedly. One night we refused to get our pajamas on and Grandad chased us with a hot poker from the fireplace. For a fifty-year old guy who’d never been around kids before, he was an expert babysitter.

I loved to explore his bedroom. Grandmom slept in the master bedroom with the luxurious master bath. Grandad occupied the secondary bedroom with a little closet of a bath across the hall. In the first chapter of my memoir, I explained that Grandmom couldn’t sleep with anyone else because she got too restless in the night. So Grandad’s room was all Grandad, a long row of short-sleeved shirts in the closet, a few fedoras that he wore when Grandmom made him go to church, his brown shoes for work and gardening. On his dresser sat a tray filled with treasures. Coins, old tissues, eyeglasses cleaners, several pocketknives that I loved to open and close. I’d eat a few chalky tums from the open roll and thumb through the thick stack of hundred-dollar bills in his wallet.

It was a well-known fact that Grandad did not like to be parted from his money. One of his tenants, Jack the hairdresser called Grandad, “Tighter than bark on a tree.” If Grandmom said she needed for money to buy groceries, he’d answer, “I’m busted.” If Mom told him she was going to buy Grandmom a microwave from him for Christmas, he’d say, “I’m busted.” When Mom would insist, he’d grudgingly hand her five dollars.

“Grandad, can I have two dollars so I can buy some school supplies?” I’d ask.

“Two dollars?” he’d say. Always followed by, “You busted?”

“Grandad, can we have a dollar for the ice cream truck?” Stacy would ask.

“A dollar? You busted?” When it was any of us kids that asked, the request was always followed by the reach into his back pocket to retrieve his wallet.

As the years passed and our tastes became more expensive, it would be like:

“Grandad, can I have a hundred dollars for a prom dress?”

“Hundred dollars? You busted?” Reach.

Today I wonder how Grandad felt about having an instant family descend on his life. Did he and Grandmom come to some agreement? Did he have doubts? I suspect he just took it in stride like he did everything in his life. Not much seemed to affect him or change his manner of operating. He lived in his own world, doing his thing, driving around Owensboro doing who knows what… looking in on his employees, checking his crops, collecting his money, stopping in at The Bowl-a-Drome in the afternoons. I bet we were kind of a surprise to him and that no one, least of all him, expected him to enjoy a bunch of unruly and demanding girls. And no one on the planet would believe Jerry Clark would reach for his wallet time and time again when asked by a blonde nine-year-old for two dollars.